Forbes is wrong when it says:

Forbes is wrong when it says:

The thing is, software talent is extraordinarily nonlinear...It’s still a kind of black magic...the 10x phenomenon, and the industry’s reliance on it, doesn’t seem to get engineered or managed away. Because the 10xers keep inventing new tools for themselves to stay 10xers...

This is folklore, not science, and it is not the view of people who actually study the industry.

Professional talent does vary, but there is not a shred of evidence that the best professional developers are an order of magnitude more productive than median developers at any timescale, much less on a meaningful timescale such as that of a product release cycle. There is abundant evidence that this is not the case: the most obvious being that there are no companies, at any scale, that demonstrate order-of-magnitude better-than-median productivity in delivering software products. There are companies that deliver updates at a higher cadence and of a higher quality than their competitors, but not 10x median. The competitive benefits of such productivity would be overwhelming in any industry where software was important (i.e., any industry); there is virtually no chance that such an astonishing achievement would go unremarked and unexamined.

This folklore arises, in part, because it is possible to be arbitrarily more productive than the worst. The software industry is no different than any other in terms of the "Peter Principle" of people rising to their level of incompetence: developers who succeed tend to move on to work on larger, more complex projects and, regrettably, not every developer or development team understands that different techniques are required at different scales. The tools and techniques that suffice for 5,000 lines of source-code don't suffice for 50,000 and what suffices with 50,000 don't suffice with half-a-million. The totally competent at one level of complexity may totally fail at the next. One of the depressing realities of being a software development consultant is regularly walking in to these situations, with their broken morale, finger-pointing, and distrust. 10x more productive? Nonsense! You're dividing by zero!

This folklore arises, in part, because it is possible to be arbitrarily more productive than the worst. The software industry is no different than any other in terms of the "Peter Principle" of people rising to their level of incompetence: developers who succeed tend to move on to work on larger, more complex projects and, regrettably, not every developer or development team understands that different techniques are required at different scales. The tools and techniques that suffice for 5,000 lines of source-code don't suffice for 50,000 and what suffices with 50,000 don't suffice with half-a-million. The totally competent at one level of complexity may totally fail at the next. One of the depressing realities of being a software development consultant is regularly walking in to these situations, with their broken morale, finger-pointing, and distrust. 10x more productive? Nonsense! You're dividing by zero!

Sure, there are tasks at which one programmer may well be an order of magnitude faster than his or her colleagues. Being well-practiced in a technique or the use of a component can easily lead to such gains. It's difficult for non-developers to understand how fundamentally plastic software is; a programmer can deliver a feature in any number of ways and even when there is broad agreement about an overall approach, there is a vast advantage in knowing "these two components turn out to be incompatible" or "that answer is easily provided by this library."

How do task-based advantages play out over the course of, say, a year? No one knows: I've never heard of a study that tried to quantify developer productivity over such a long timescale. The problem of even defining productivity at such a timescale is ample cause for argument. Professional software development is a team sport, and most development managers have experienced a trade-off of a developer with technical skills but less-than-desired soft skills. Conversely, time spent away from the keyboard actually working with users often leads to far more value than would be achieved by coding away and checking later.

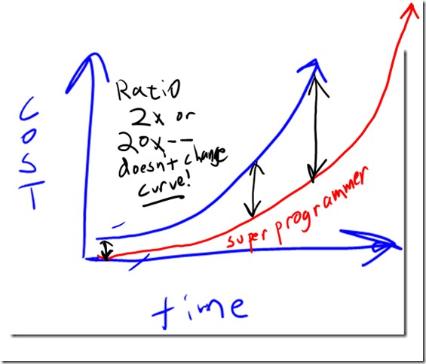

None of this is to say that there are not individual differences in productivity. Based on the programmers I've met over the course of 20 years of working with software teams, I think that over long timescales, the top 5% of programmers are probably 2-3x as productive as median programmers (and I don't think anyone in industry is 10x median: industry couldn't provide sustenance for such a creature). I tend to think that this is a combination of inherent talent, the speed with which they can switch between tasks and techniques, and temperament.

I get stirred up about this folklore because it has major consequences. An industry where excellence is 10x median performance ought to be structured very differently than an industry where excellence is 2-3x median.

I get stirred up about this folklore because it has major consequences. An industry where excellence is 10x median performance ought to be structured very differently than an industry where excellence is 2-3x median.

Variations in productivity compound: over the course of several release cycles, even in a world without super-programmers, the excellent team can crush the less-the-average (even putting aside the uncommon, but not vanishingly rare, competition that truly has zero productivity or is even in negative making-things-worse mode).

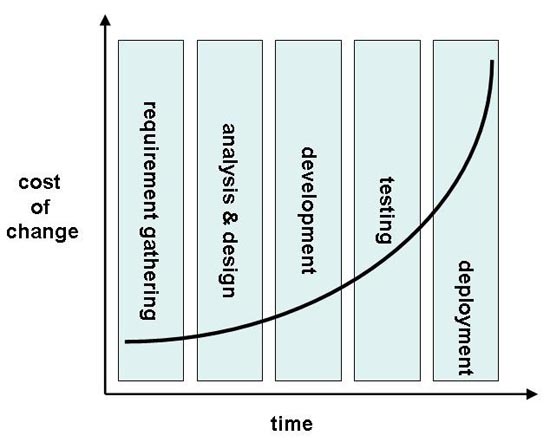

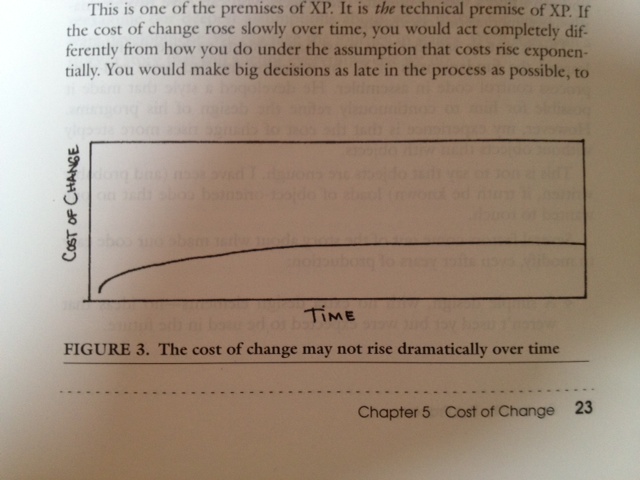

But even if there are real super-programmers, Forbes still is wrong about "developernomics." The real issue in software development is which of these two charts correctly describes the cost of fixing a defect over time:

The first is the Boehm curve and the second is the Beck curve. The Boehm curve describes the view presented in "Software Economics" and holds that the cost of fixing a defect rises exponentially over time: it is cheap to correct a mistake when sitting around a table gathering requirements, more expensive to fix during initial coding, more expensive to fix late in testing before release, very expensive to fix after release. The Beck curve describes the view presented in "Extreme Programming Explained": while it's still cheapest to fix a mistake before a line of code is written, fixing a two-year-old defect in production code is not really that much more expensive than fixing the defect 10 minutes after it's first introduced into code.

There is much to be said about these curves, but the crucial point is this: individual programmer excellence, whether 10x median or 2x, does not drive organizational software productivity. Any team, no matter how talented the individuals, whose costs follow the Boehm curve will, over time, lose to any team, no matter how mediocre the individuals, whose costs follow the Beck curve. It's just a matter of where the cross-over occurs.

Does industry have teams whose costs follow the Boehm curve? Yes, absolutely. Does industry have teams whose costs follow the Beck curve? I'm not sure that the constant-over-time flatness is realistic, but absolutely teams can bend the curve towards the ideal. Call it "process-nomics" or "team-nomics" or, hell, call it "developernomics" because it is developer-centric. The problem with the Beck curve from the management perspective is that to achieve that curve, you have to give up traditional project management controls. Gantt charts don't work with agile development. You can't do fixed-price, fixed-feature, fixed-time budgeting. You can't sign off on requirements and wait around for teh awesome to appear under the Christmas tree.

Management hates giving up that stuff so much that they would rather continue chasing unicorns and 10x super-programmer teams and magical complexity-free programming models. So now, because of this stupid Forbes article, you're going to have to explain to your bosses why it's stupid and off-putting to write a "we're looking for rockstars!" job ad and why you shouldn't either jump on the first "ninja" to walk in the door or spend a year filling a position and they're going to be pissed when you ask the obvious "if you believe this, then which of our developers is going to be paid \$700,000 per year?"

And the fact that they don't structure salary like that? It shows that, not far from the surface, they know its bullshit.

Update: If the subject’s of interest to you, you might enjoy (or despise) the column on the subject I’ve been writing for SD Times for the past decade.

Update: A little less rant-y follow-up post Why 10x Ticks Me Off

Update: Moneycode vs. Developernomics